Evenings don’t have to spiral. In this guide: 10 calm-down scripts, a 90-minute routine that cuts sundowning, and a fridge-ready safety checklist.

Grab the PDF to print and keep by the chair.

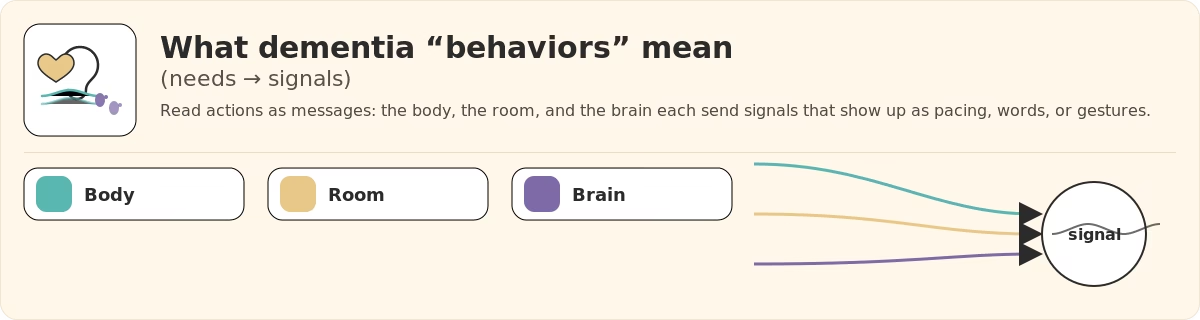

What Dementia “Behaviors” Really Mean (Needs → Signals)

Here’s the truth: when someone with dementia paces, argues, calls out, or says “I need to go home,” it’s not defiance. It’s communication.

Why? The brain has fewer reliable words and less processing power. So the body talks instead—through movement, tone, and patterns across the day.

And almost every tough moment traces back to three roots:

1) Unmet needs (the body is asking)

Think physiology first.

- Hunger/thirst → looks like restlessness or rummaging.

- Full bladder/constipation → standing up and down, tugging at clothes, snappy irritability.

- Pain (hips, back, feet, mouth) → refusing care, calling out, or lashing out.

- Too hot/cold + end-of-day fatigue → sharp language, motor agitation.

As interoception (sensing internal states) and language fade, signals go indirect. You’ll “hear” it in pacing, voice, and timing—not neat sentences.

2) Environmental load (the room is too much)

Filtering sights and sounds gets harder.

- Glare, shadows, mirrors/dark glass → can look like strangers or doorways.

- TV chatter + overlapping conversations + clutter → a traffic jam for the senses.

- Late-day light makes it worse: reflections grow, contrasts spike, wayfinding slips.

What reads as “wandering” is often search behavior in a space without clear cues about where to be or what to do.

3) Brain changes (capacity has shifted)

Dementia alters how information is received, stored, and processed. That shapes what the person perceives, what it feels like, and how strongly it shows up.

Memory gaps

Recent context drops → “Where am I?” “I need to go home.”

Disorientation

Time/place map fuzzy → morning at 6 pm; looking for old house.

Aphasia

Words harder → needs move to gestures, pacing, vocal tone.

Memory gaps (context disappears)

- What it is: Short-term memory can’t “hold the scene.” Recent facts (where we are, what just happened) drop out.

- How it shows: “Where am I?” “I need to go home.” Asking for people who aren’t present. Repeating the same question because the previous answer didn’t “stick.”

- What it signals: They’re trying to re-anchor themselves when the story of now won’t load.

Disorientation to time/place (no stable map)

- What it is: The internal clock and location compass get fuzzy.

- How it shows: Believing it’s morning at 6 pm; preparing for work despite retirement; looking for a childhood house.

- What it signals: Baseline vigilance—when time/place are uncertain, the nervous system treats ordinary cues as potential threats.

Language changes — aphasia (words get harder)

- What it is: Finding, forming, and understanding words takes more effort (aphasia).

- How it shows: “That thing… the thing!”; switching to gestures, tone, pacing; mixing up nouns; stopping mid-sentence.

- What it signals: Needs are still there, but they travel via movement, facial expression, and vocal tone more than precise phrases.

Agnosia

Seeing ≠ recognizing → mirrors look like people; patterns like holes.

Executive function

Fewer “brakes” → feelings turn into actions faster.

Sundowning

Late-day surge (3–8 pm) → pacing, “go home” loops, irritability.

Visual–perceptual changes — agnosia (seeing ≠ recognizing)

- What it is: The eyes see, but the brain misidentifies or can’t interpret (agnosia).

- How it shows: Mirrors look like “a stranger in the room”; patterned carpets become “holes”; dark doorways read as tunnels.

- What it signals: The world contains false alarms—ordinary reflections or patterns can feel like obstacles or intruders.

Executive function losses (the brain’s “manager” is tired)

- What it is: Planning, prioritizing, shifting tasks, and impulse control weaken.

- How it shows: Jumping from task to task; grabbing for a door now; difficulty following multi-step instructions.

- What it signals: Feelings convert to actions faster; fewer brakes, fewer “let me think this through.”

Sundowning (late-day surge)

- What it is: A predictable rise in restlessness/confusion as fatigue, circadian rhythm changes, and sensory build-up stack up.

- How it shows: Pacing, “go home” loops, irritability, shadowing a caregiver from room to room—most often between 3–8 pm.

- What it signals: The system is overloaded and running on low reserves; small ambiguities feel big, and minor irritants loom large.

Bottom line

Dementia behaviors are signals about comfort, safety, and meaning in a world that’s harder to read. They point to:

- the body’s state (hunger, pain, elimination, temperature, fatigue),

- the room’s demands (light, noise, visual complexity, unfamiliarity),

- the brain’s changing capacities (memory, language, perception, executive control).

Read the moment as message first, not misconduct—and you’re set up for everything that follows.

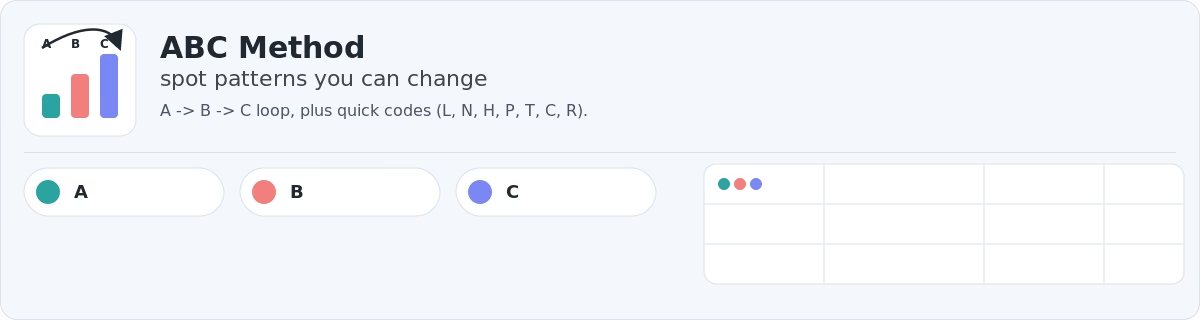

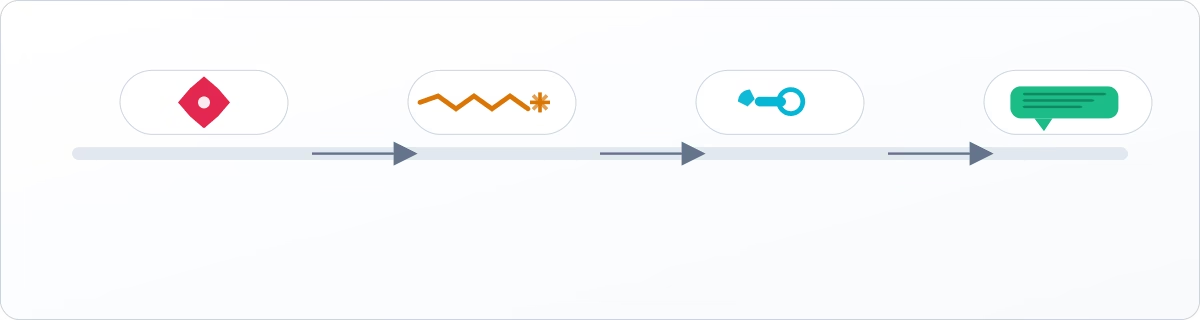

ABC Method: Spot Patterns You Can Change

Why does it help? Behaviors are communication. The A–B–C frame turns a chaotic moment into a pattern you can see and adjust. You note what came before (A), what you saw (B), and what followed (C). Over a few days, repetitions jump out—same time window, same trigger theme, same responses that help or hurt.

A — Awareness (what came right before)

Think context + conditions in the minutes or hours leading up to the behavior.

- Time & timing: time of day; too close to nap; long gap since snack/fluids.

- People: visitors; unfamiliar caregiver; overlapping conversations.

- Environment: L (lighting glare/shadows), N (noise/TV), visual clutter, mirrors/windows at dusk.

- Body needs: H (hunger/thirst), T (toilet), C (constipation), P (pain?)—hips, back, feet, mouth.

- Tasks & demands: confusing steps, rushed requests, and sudden transitions.

- Routine changes: R (routine shift)—appointment, medication time moved, travel, daylight savings.

Quick codes for your log: L, N, H, P, T, C, R (use multiple codes ff several apply).

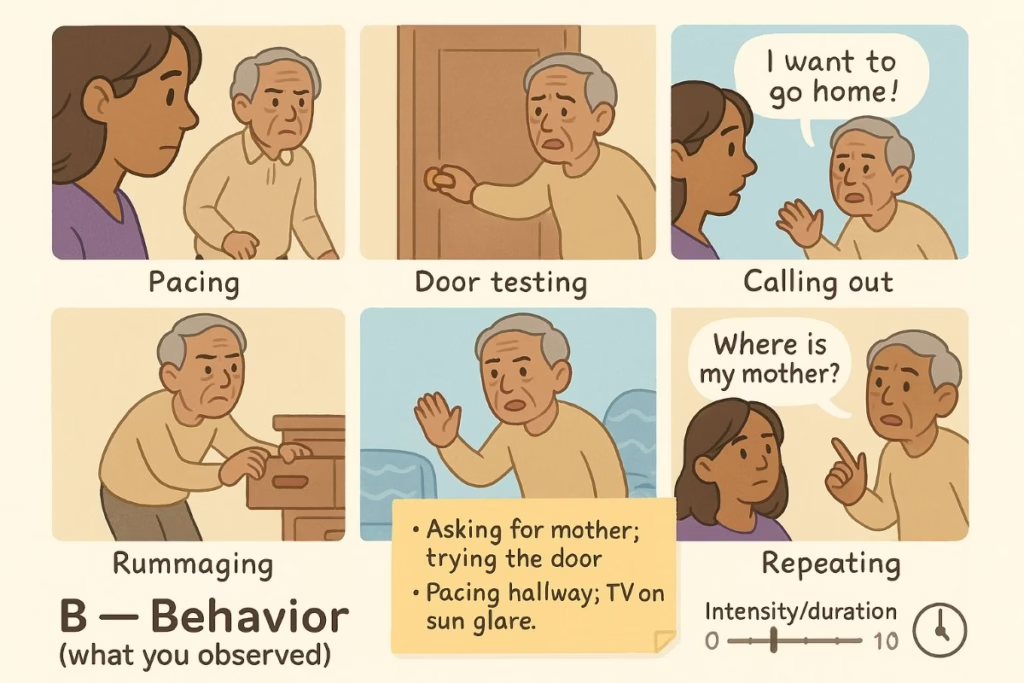

B — Behavior (what you observed)

Write what was visible and concrete, not an interpretation.

- Examples: pacing, door testing, calling out, saying “I want to go home,” rummaging through drawers, refusing a wash, taking off clothing, and repeating a question.

- Describe in one line: “Asking for mother; trying the door,” or “Pacing hallway; TV on; sun glare.”

- Note the intensity/duration if possible (e.g., 7/10 for ~15 minutes).

Keeping B descriptive (not judgmental) makes patterns easier to compare across days.

C — Control (what happened after)

Capture the immediate aftermath—what you did, what they did, and whether things escalated or eased.

- Your actions: what you changed, said, or offered (e.g., dimmed lamps; turned off TV; brought tea; gave two choices).

- Their response: calmer, same, or more agitated; any shift in pacing/voice.

- Outcome tag: Helped? Y/N + one short note (e.g., “calm in 4–5 min” or “escalated after TV laugh track”).

This is not about judging; it’s about seeing which consequences reliably land well.

How to capture it in 90 seconds (7-Day Log workflow)

- Time + place: “5:20 pm, kitchen.”

- Antecedent quick-codes: choose all that fit (L, N, H, P, T, C, R).

- 1-line behavior: “Asking for mother; tried door.”

- What you tried (brief): “Dimmed lamps; tea + crackers; ‘safe with me’; slow playlist.”

- Outcome: Y/N + one sentence.

Short entries you’ll actually write beat perfect entries you’ll never keep up with.

Reading your patterns (after three days)

- Time window: Circle clusters. If most entries hit 4:30–6:00 pm, you’ve found a vulnerable window.

- Trigger theme: Tally codes. If H shows up repeatedly, late-day hunger/hydration is likely; if L dominates, lighting/glare is a top suspect; if R appears, routine stability matters.

- Response winners: Star the actions that helped ≥50% of the time. Those are your first-line responses next week.

Turn the log into tiny experiments

- One change per day. Name it in the log: “Lamp-only after 4 pm.”

- Hold 3–4 days. Give each change time so you don’t discard a quiet winner.

- Bundle wins. When two single changes help, try them together during the vulnerable window.

These are micro-SOPs—small, repeatable steps you can teach to any helper.

When ABC says “call the clinic”

If behavior suddenly shifts over hours or days or appears with fever, new/worse pain, urinary changes, falls, head injury, chest pain, or stroke-like signs, treat it as a medical red flag and contact your clinician/urgent care.

Bottom line

ABC makes behavior legible. A shows the likely fuel, B names what you actually saw, and C records what nudged the needle. With a week of brief notes, you’ll know when trouble tends to start, what sets it off, and which responses consistently help—turning guesswork into a simple plan you can repeat.

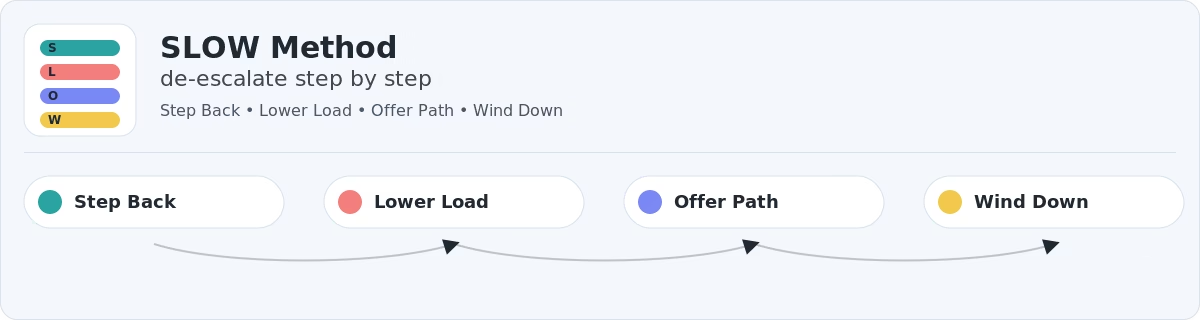

SLOW Method: De-escalate Step by Step

When agitation appears, run the same calm play every time: SLOW — Step back → Lower the load → Offer a path → Wind down. This sequence reduces threat signals in the body and environment before you ask for anything new.

1) Step back (5–10 seconds)

Body position. Turn your torso so you’re halfway between side-by-side (0°) and straight on (90°)—about 45° toward them. Close enough to connect, not confront.

Hands (simple options):

- One-hand rest: Let one hand hang at your side; rest the other lightly across the opposite forearm (wrist area), fingers loose.

- Two-hand option: Lightly clasp both hands at belly level, with elbows soft and palms slightly open.

- Seated: Rest both hands on your thighs, palms down.

Keys: hands visible, relaxed, still—no pointing or fidgeting.

Breathing cue. Take one slow, audible breath. People often mirror the pace and tone of the person with them; your breath sets the metronome.

Anchor words. Use one short sentence that communicates safety without debate: “I’m here. You’re safe.” Then pause. Let the words land before moving on.

2) Lower the load (remove the “now” stressor)

Lighting. Turn off harsh overheads. Switch on two warm lamps to even out shadows. Close curtains to cut reflections from windows and mirrors, especially at dusk.

Noise. Mute the TV. Ask others to pause side conversations or move to another room. Reduce visual clutter on the immediate surface so the brain has fewer items to sort.

Physiological load. Offer a warm, caffeine-free drink and a simple snack. Ask one practical choice: “Bathroom first or tea first?” You are shrinking the number of competing demands so the nervous system can downshift.

3) Offer a path (two calm choices + a purpose)

Why does it calm? Anxiety often rises when a person has no clear next step. Two gentle choices restore agency; a simple purpose channels energy into something familiar.

Choice scripts.

- “Would you like your sweater or a blanket?”

- “Should we look at these photos now, or after tea?”

Purpose scripts.

- “Could you help me sort the towels? You’re great at it.”

- “Let’s line these spoons the way you like them.”

Keep choices concrete and equivalent; avoid “right answer” traps.

4) Wind down (anchor to safety + routine)

Sensory landing. Put on a slow playlist of music (45–60 BPM) or play white noise at a low volume. Keep the light at lamp-level. Sit together side-by-side or at a slight angle.

Closing words. “Let’s make it comfortable. After tea, we’ll get ready for bed.” The routine promises predictability—exactly what a stressed brain wants.

Decision Paths for Common Moments

A) “I need to go home.” (often signals overload or feeling unsafe)

Quick check. Is dusk starting? Is the TV loud? Is hunger or thirst likely?

Do now. Dim the room, mute the TV, offer a snack/tea, open a photo book from their home era, and hand them a small task.

Words. “You’re safe here. Tell me about your home—what did your kitchen smell like? Could you help me line up these spoons like you used to?”

If it escalates. “I’ll grab your tea and the soft blanket; be right back.” Step out for 30–60 seconds, return quietly, and sit beside them (without blocking the way).

B) Repetitive questions (“Where’s mom?” every 2 minutes)

Do now. Answer aloud and add a visible cue (such as a sticky note/whiteboard) where they’re looking.

Words. “You’re safe—she’s at work and back later.” Place note: “Mom is at work—back later.”

Redirect. “While we wait, could you help me fold these?”

Avoid. Long explanations or corrections about time/death—they often increase distress.

C) Refusing care (wash, meds, bed)

Quick check. Was the ask too complex? Is the bathroom cold? Are they chilled?

Do now. Warm the room; break the task into one short step; offer two choices; model the action.

Words. “I’ll wash my face first, then it’s your turn. Would you like the warm cloth or the soft one?”

D) Shadowing or pacing

Do now. Move with them; match pace; add purpose rounds: plants → windows → kettle.

Words. “Let’s do our rounds. We check the plants, then the windows, then the kettle.”

Landing. Finish in the bedroom/living room with lamps on and music playing at a low volume.

What not to do (and what to do instead)

- Don’t argue or correct reality. Do validate the feeling and step into their frame of reference.

- Don’t fire multiple questions. Do ask one clear sentence and wait 5–10 seconds.

- Don’t touch from behind or suddenly. Approach at/below eye level, 45°, with hands visible.

- Don’t promise outcomes you can’t control. Do promise presence: “I’m staying with you.”

End-of-episode landing script

Close with reassurance plus sensory cues:

“That felt hard. You did well. Let’s mark this done and make it cozy.”

Then dim the lights, lower the music, add a blanket, and let the quiet settle.

By running SLOW the same way each time, you create a predictable arc: safety first, stressors lowered, clear next step, gentle landing. The repetition becomes its own comfort—and over days, many episodes shorten and soften.

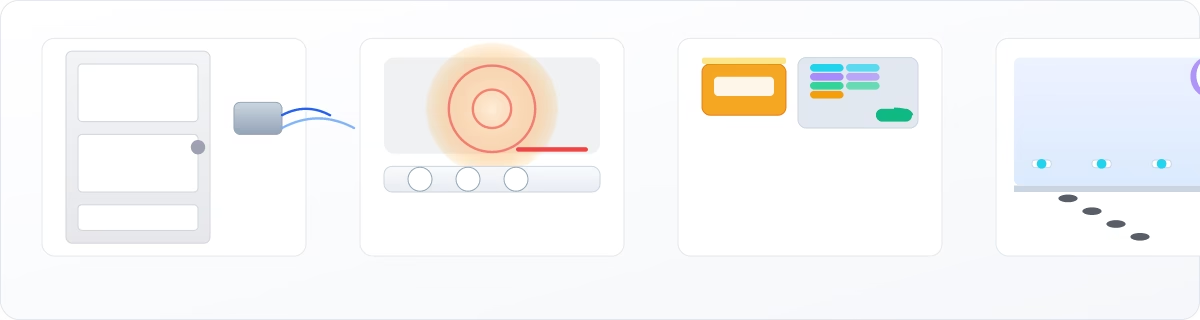

Evening Environment Design (Lighting · Noise · Clutter)

A calm evening space lowers the brain’s workload and gives the body simple cues: it’s safe, and it’s time to settle. Think in three layers—light, sound/visual load, and layout/safety—and set them up the same way every day.

Lighting (comfort over brightness)

- Shift to lamp-level, warm light by mid-afternoon. Use 2700–3000K bulbs in table/floor lamps; avoid harsh ceiling cans and blue-white glare.

- Close curtains before dusk to cut reflections in windows. Reflections and silhouettes can look like strangers or doorways. If mirrors cause a startle response or the feeling that “someone’s in there,” cover them after 4 pm or relocate them.

- Layer light sources. Two lamps placed at opposite sides of the room reduce shadows; a third small lamp near the chair aids reading without flooding the space.

- Night navigation. Place a soft night-light along the path to the bathroom/bed—enough to see contrasts, not bright enough to wake fully. Avoid motion lights that snap on too bright.

Soundscape (noise down, signal clear)

- TV: Off is best. If it must stay on, use calming visuals (such as nature or slow travel) with subtitles and a low volume; avoid laugh tracks, news, or fast-paced ads.

- One voice at a time. Overlapping conversations force extra processing and often trigger “get me out of here” behavior. Nominate a “lead voice” and keep the rest quiet.

- Appliances & pets. Run dishwashers, blenders, and vacuums earlier in the day. If pets get excited at the doorbell, add a “quiet zone” during the wind-down hour.

- Soothing backdrop. A slow playlist of music (45–60 BPM) or low white noise can help smooth sudden spikes from street sounds.

Visual load & clutter (less to sort)

- Clear the activity surface (table/side table) before 4 pm—today’s task only. Put other piles into a bin with a lid so they don’t “call” for attention.

- Simplify sightlines. Too many knick-knacks and mixed patterns make rooms visually “busy.” Keep a few meaningful objects visible; rotate others into storage.

- Color contrast helps. Use placemats or a tray that contrasts with the table so cups/utensils are easy to see and grasp.

Comfort cues (the room says “cozy”)

- Warm, non-scratchy layers within reach; place your favorite blanket where it is visible (draped over the landing chair).

- Create a small “comfort basket” with items such as hand lotion, soft cloth, lip balm, photo cards, and a large-print poem/prayer. When agitation flickers, the basket offers immediate, familiar anchors.

- Temperature: Aim for a slightly warm evening; cold rooms increase muscle tension and resistance to care.

Wayfinding & safety (move easily, feel secure)

- Clear a 36″ walking path from chair → bathroom → bed. Remove trip hazards (loose rugs, cords).

- Contrast for depth. Bedding that contrasts with the floor and a towel that contrasts with the sink help with depth perception.

- Exits: Add a door chime to exterior doors so you hear movement without hovering.

- Kitchen boundaries: After dinner, make the kitchen visibly “closed” (stove knobs removed or covered if needed, lights off, simple “kitchen closed” sign).

- Visual cues, not lectures. Labels on drawers (CUPS, SPOONS) and a bedside card (“Toilet → Bed”) guide without debate.

Make it a repeatable setup

- Same time, same order: lamps on → curtains closed → TV off/visuals calm → table cleared → music low. Consistency is its own therapy.

- Prep box: Keep spare warm bulbs, nightlights, extra lamp, white-noise device, and tape/covers for mirrors in one bin so substitutes are easy to access.

- Small spaces tip: if you have one multipurpose room, define an “evening corner”—chair + lamp + blanket + tray—so the body knows where to land.

This environment doesn’t just look calmer—it reduces the brain’s sorting tasks, which often lowers restlessness before it starts.

Snack Plan: Hydration + Protein Between 3–5 PM

Late afternoon is a vulnerable window: blood sugar dips, fluids are low, and fatigue builds. A small, familiar, and easy-to-chew snack, paired with hydration and a bit of protein, can help smooth the transition to the evening. Keep portions modest so dinner still happens; think comforting, not heavy.

Principles

- Pairing: Every snack includes fluids and protein (e.g., tea and yogurt; water and cheese).

- Texture & familiarity: choose foods they’ve loved for years; avoid crumbly, hard, or mixed textures if chewing/swallowing is tricky.

- Caffeine cut-off: avoid caffeine after noon; choose warm, caffeine-free options (herbal tea, warm milk).

- Steady timing: aim for 3:30–4:30 pm daily; predictability reduces late-day dips.

- Safety notes: If there are fluid/sodium/diabetes restrictions, follow the clinician’s plan. For dysphagia, use thickened liquids and avoid mixed textures.

Starter ideas (mix & match)

- Yogurt + berries (or applesauce)

- Cheese + crackers (or soft bread)

- Banana + peanut butter (thinly spread)

- Warm caffeine-free tea + soft cookie

- Applesauce + cinnamon

- Soup cup (split-pea, tomato, chicken; warm, smooth)

- Hummus + soft pita

- Oatmeal cup with honey or mashed banana

- Cottage cheese with peaches or pears (soft)

Simple weekly rotation (example)

- Mon: yogurt + berries; herbal tea

- Tue: cheese + crackers; water with lemon

- Wed: soup cup + soft roll

- Thu: banana + peanut butter; herbal tea

- Fri: applesauce + cinnamon; water

- Sat: hummus + soft pita; herbal tea

- Sun: oatmeal cup + honey; water

Hydration cues

Offer small, frequent sips; a favorite mug often helps. Aim for light-colored urine unless fluids are restricted. Add slices of lemon, cucumber, or a splash of juice for taste without a sugar spike.

Presentation tips

Serve on a contrasting plate/tray so items are easy to see. Keep only the snack and drink on the table—clutter competes for attention. Sit together for a few minutes; the shared ritual can be as calming as the food.

7-day Evening Routine (Filled Example + Template)

A predictable wind-down cues the body for safety and sleep. Use this planner to script the 90-minute run-up to bedtime. Keep it the same most days; small variations (such as a snack or task) keep things familiar but not boring.

Each day’s 90-minute routine

Snack strip (3:30–4:30 pm)

Mon yogurt+berries · Tue cheese+crackers · Wed soup+soft bread · Thu banana+PB · Fri applesauce+cinnamon · Sat hummus+pita · Sun oatmeal+honey

T-90 → T-60 — Settle & Snack

Lamps on, curtains closed, calm visuals. Quiet table task (photo cards; fold 2 towels). Serve the day’s snack + drink.

T-60 → T-40 — Familiar Doin

One easy chore (water plants; organize “job” box; sort cards). Start slow playlist (45–60 BPM).

T-40 → T-25 — Wash & Comfort

Warm wash/shower. Comfy clothes. Toilet routine (note patterns).

T-25 → T-10 — Dim & Reminisce

Dim to lamp-only. Short poem/prayer or one photo-album story. White noise low.

T-10 → Bed — Safety & Reassure

Meds as prescribed. Safety sweep (stove, doors, night-lights). Landing words: “You’re safe; I’m nearby.”

Legend: T-90/60/40/25/10 = 90/60/40/25/10 minutes before bedtime; → Bed = lights-out/bedtime.

Download the 7-day Evening Routine (PDF)Tip: Put these five blocks on a 5-line index card and clip it to the fridge. Same order every day; vary only the snack/chore/story.

How to use it

- Start on time: Begin before agitation usually appears.

- One change at a time: Adjust a single block (e.g., different chore) and hold for 3–4 days.

- Mark wins: If a block reliably shortens or softens episodes, star it and repeat.

- Shareable: Post this in the evening area so any helper can follow the same rhythm.

Troubleshooting Matrix (Problem → Trigger → Fast Fix → Script)

Use this quick map when a moment starts to spiral. Read left to right, try the fix, say the line, and note the result in your log.

Trigger Checklist (Scan at 3–4 PM)

Print the 1-page checklist and post it on the fridge. Fix one or two items at a time and watch your 7-Day Log to see which changes actually help.

Download the Trigger Checklist (PDF)Home Safety Mini-audit (Doors, Stove, Meds, Night Wandering)

Do a quick safety sweep, room by room.

Focus on the four evening hot spots: doors/wandering, kitchen/stove, medications, and night wandering.

Make small, visible tweaks. Then repeat them every night—consistency is your safety net.

1) Doors & wandering (prevent slip-outs without hovering)

- Audible awareness: Add simple door chimes to exterior doors so you hear movement without shadowing. A battery or plug-in is fine; test it weekly.

- Lock placement: Move or add locks higher or lower than eye level to reduce automatic opening. Avoid anything that traps people in during an emergency—caregivers must be able to open doors quickly and easily.

- Visual cues: Place a stop sign or a curtain over glass panes at dusk; many people read these as “not now.” A small bench or plant near the door can cue “this is a resting spot, not an exit.”

- Identification: Keep a medical ID bracelet or pendant on; store an up-to-date “lost-and-found” photo + contact on your phone and on paper near the door.

- Timing: Shift walks and fresh air earlier (before dusk) so the body doesn’t push for an outing at the most confusing hour.

- Night routine: Set nightlights along the bedroom-to-bathroom path and keep exits darker (the body follows light toward the bathroom, not the door).

2) Kitchen & stove (reduce burn/fire risk during the wind-down)

- Shut-off habits: After dinner, do a “kitchen closed” ritual: appliances off, counters cleared, lights off, and a small sign on the stove. Rituals are remembered even when facts aren’t.

- Hardware helps: Use auto-shutoff plugs or stove safety devices where appropriate. If unsupervised, remove or cover stove knobs. Unplug small appliances (toaster, kettle).

- Visual simplification: Clear counters to two or three safe items (e.g., a fruit bowl, a water station). Fewer objects = fewer impulses to “get to work.”

- Storage: Place cleaning products and sharp tools out of sight and reach. Use child-proof latches if needed.

- Night hydration station: Keep a labeled water cup on a tray away from the stove so thirst doesn’t lead someone to fiddle with burners.

3) Medications (accuracy beats improvisation)

- One home base: Use a single, locked organizer (such as a weekly or daily blister) rather than multiple bottles. This prevents double-dosing and scavenger hunts.

- Same time, same words: Dose on a consistent schedule and use the exact brief phrase each time. Novelty invites debate; routine invites acceptance.

- No PRN “calming”: Never add extra pills or alcohol to “settle” agitation. If evenings are chronically difficult, document patterns in your 7-Day Log and discuss with the prescriber.

- Chain of custody: If multiple helpers, keep a med sign-off sheet (initials/time) with the organizer. Only one person should prepare doses.

- Storage & disposal: Lock up controlled meds; remove discontinued or expired ones so they don’t reappear by mistake.

4) Night wandering (safe passage without restraints)

- Light the route: Use low, warm nightlights from bed to bathroom and back to bed. Avoid bright motion lights that fully wake the brain.

- Clear the path: Ensure a 36″ walkway free of cords, ottomans, or throw rugs. Add non-slip backing where needed.

- Bedroom cues: Keep the favorite blanket and a visible water cup in the same spots nightly; the eye recognizes “my place to land.”

- Gentle alerts: Consider pressure mats or discreet door sensors that send notifications to your phone—use them sparingly to avoid alarm fatigue.

- Clothing & comfort: Warm socks, easy-on layers, and a pre-warmed bathroom (if possible) reduce reasons to roam.

Keep it accountable

- Do this audit once, then re-check monthly (bulbs burn out, tape loosens).

- Add a safety line to your evening checklist: Doors chime on, Kitchen closed, Meds set, Path lit.

- Log near-misses (“turned stove at 8:10 pm”)—they’re early warnings to adjust the setup, not failures.

When to Call for Help (Red Flags)

If any of the signs below appear, don’t wait—call your clinic/doctor, an after-hours line, or urgent care/911 as noted. Trust your gut if something feels suddenly different.

1) Sudden change in thinking or alertness (hours–days)

Why it matters: Could be delirium from infection, dehydration, medication side-effects, or stroke.

Action: Call same-day/urgent care.

Examples:

- Calm yesterday → confused, agitated, drowsy today.

- New hallucinations or rapid cycling between sleepy and restless.

- Not recognizing home when they usually do.

2) Signs of infection or dehydration

Action: Call same-day; fever with confusion is urgent.

Examples:

- Fever or chills (any temp change with confusion counts).

- Painful urination, urgency, foul odor; no urine for ≥ 8 hours.

- Very dry mouth, dizziness on standing, dark urine, minimal fluid intake.

3) Chest pain or breathing trouble → 911

Why it matters: Possible heart attack or pulmonary issue.

Examples:

- Pressure/heaviness in the chest, pain in the arm/jaw/back, shortness of breath, sweating, nausea.

4) Stroke signs → 911 (time = brain)

Use FAST to guide: Face droop, Arm weakness, Speech slurred/strange, Time to call.

Examples:

- Sudden one-sided weakness/numbness, new slurred speech, severe “worst-ever” headache.

5) Head injury or significant fall

Call urgent care/911 (especially if on blood thinners or hit the head).

Examples:

- Hit head with new confusion, vomiting, severe headache, or drowsiness.

- New inability to bear weight, obvious deformity, severe hip pain.

6) Dangerous agitation or behavior

Call urgent care/911 if safety is at risk.

Examples:

- Trying to leave home, into traffic, or cold, physically aggressive, or destroying the stove/meds.

7) No intake or bowel issues

Same-day call; ER if severe pain/vomiting.

Examples:

- No food or fluids all day despite tries.

- No bowel movement for several days with belly pain, vomiting, or swelling (possible obstruction or severe constipation).

8) Medication problems

Same-day call; poison control/ER if overdose suspected.

Examples:

- Missed multiple doses of critical meds (e.g., heart, seizure).

- Took extra doses or wrong medication; new rash, facial swelling, or wheeze after a new drug.

Before you call, please bring your medication list, vital notes (temperature, fluid intake, and urine output times), and your 7-Day Log entry. Brief, concrete details enable clinicians to act quickly.

Caregiver Confidence (Mindset, Boundaries, Self-reset)

Mindset (what you control).

Confidence isn’t pretending it’s easy; it’s choosing a stance you can repeat under pressure. Three anchors help:

- Message, not misconduct. Behavior = communication. You are a decoder, not a referee.

- Progress over perfection. “Shorter, softer, fewer” is a win—shorter episodes, softer intensity, fewer per week.

- Rituals beat willpower: the same evening setup, the same words, the same order. Consistency carries you when energy dips.

Boundaries (protect the container).

Calm care needs edges. Set them early and state them plainly:

- Non-negotiables: safety checks (stove, doors, meds), no driving, no alcohol as “calm,” no arguing facts.

- Time limits: put a cap on stressful loops (e.g., 10 minutes of searching → switch to a task).

- Roles: one “lead voice” at a time; others step back. Rotate evening duties so no one burns out.

- Visitor rules: quiet hours after 4 pm; one visitor at a time; “goodbyes before dusk.”

Quick self-reset (60–90 seconds).

Use before you intervene—or mid-episode if you feel your fuse shortening.

- Posture: feet planted, unlock knees, drop shoulders, soften jaw.

- Breath: inhale 4, exhale 6—repeat 5 times; whisper “slow” on the exhale.

- Gaze: pick a still point (lamp edge); let your eyes settle there for two breaths.

- Phrase: one quiet line you believe: “We can go slow,” or “Safe and steady.”

- Re-enter: one short sentence + two calm choices.

Micro-support plan (daily minimums).

Confidence holds when basics hold:

- Fuel: snack + water for you, too; caffeine cutoff.

- Tiny breaks: two 5-minute offloads (doorway stretch, balcony air, hallway laps).

- One text check-in with a friend/sibling—accountability, not venting.

- End-of-day note: one line in the log: What helped once today? Repeating small wins builds trust in your process.

Bottom line: confidence is a skill, not a mood. Clear edges, tiny resets, and repeatable rituals help you stay reliably calm—even on hard days.

Tech That Helps (Quiet, Simple, Predictable)

Door chimes & entry alerts (awareness without hovering)

- What they do: Play a tone when an exterior door opens so you can respond early without standing guard.

- Look for: Simple plug-in or battery units, adjustable volume, distinctive tones, and a silent night option. If you have multiple doors, choose chimes that allow you to name zones (e.g., Front/Back) or use different tones.

- Setup tips: Mount sensors at the top of the frame, test weekly, and keep spare batteries in the same drawer.

ID wearables & gentle location tools (safety if someone slips out)

- What they do: Provide identification and, in some cases, limited location help. Start with a medical ID bracelet (name, key medical info, contact).

- Optional: Basic trackers can notify a caregiver’s phone when someone leaves a safe zone. Use only with consent and keep expectations realistic—GPS can drift, and battery life is a crucial factor.

- Privacy & dignity: Explain the purpose (“helps us find each other quickly”) and choose comfortable, non-stigmatizing designs.

White-noise & sound shaping (smooth the soundscape)

- What it does: Masks sudden spikes (TV ads, street noise) and creates a steady, low “auditory blanket.”

- Look for: Devices or apps with continuous (not pulsing) sound, independent volume control, and a simple on/off button.

- Placement: One unit in the evening room, one near the bedroom; keep volume low enough to allow conversation.

Warm-light & visual comfort (signal “evening,” not “task mode”)

- What they do: Reduce glare and blue-white stimulation that can fuel late-day restlessness.

- Look for: 2700–3000K bulbs; table/floor lamps with diffusers; dimmers, if possible.

- Add-ons: Night-lights along the bed→bath path; window films or sheer curtains to tame reflections; mirror covers for dusk.

Simple visual cues & reminders (reduce verbal load)

- What they do: Replace repeated explanations with visible answers.

- Tools: Magnetic whiteboard for “Mom is at work—back later,” large-print clock with day/part-of-day display, label tape for drawers (“CUPS,” “SPOONS”).

Safety sensors (use sparingly, test regularly)

- What they do: Quietly alert you to risk without startling the person.

- Options: Bed/door pressure mats that ping a phone, stove auto-shutoff adapters, water-leak sensors near the bathroom.

- Rule: Start with one alert to avoid alarm fatigue; set a weekly “tech check” (batteries, tones, volumes).

Myths & FAQs

Bottom line: Pick one tool per problem, keep it simple, and build a small “evening kit” (spare bulbs, chime batteries, whiteboard markers). The best tech is quiet, predictable, and supports your routine—not the other way around.

1) “Sundowning means they’re being difficult.”

Reality: It’s not willful misbehavior—it’s the nervous system struggling with fatigue, changing light, and sensory load. Behaviors are distress signals.

Try instead: Read the moment as a message (needs → signals). Adjust light, noise, and routine before reasoning or lecturing.

2) “More light = less confusion.”

Reality: Bright, cool/blue overheads can increase agitation at dusk by creating glare and harsh shadows.

Try instead: Use warm, lamp-level lighting (2700–3000K), close curtains before dusk, and cover mirrors that cause misperception.

3) “If I keep correcting them, they’ll understand.”

Reality: Repeated reality checks (“You live here now”) often raise anxiety and prolong the episode. Memory and orientation losses make logic a weak tool in the moment.

Try instead: Validate the feeling (“You’re safe”), then redirect with a simple choice or familiar task. Save explanations for calm times.

4) “Naps are bad—keep them awake all day.”

Reality: Long or late naps (after ~2 pm) can worsen evening agitation, but brief, earlier naps can improve mood and energy.

Try instead: A 20–30 minute rest before 2 pm; pair with an afternoon snack and gentle movement later.

5) “Medication is the main fix for sundowning.”

Reality: There’s no universal pill for evening agitation, and “as-needed” sedatives can carry risks (falls, paradoxical agitation). Environment and routine changes are first-line.

Try instead: Standardize the 90-minute wind-down, address triggers (hydration, constipation, pain), and discuss persistent patterns with the clinician using your 7-Day Log.

6) “Keeping them busy all evening prevents problems.”

Reality: Over-programming can add cognitive load and backfire. People need predictable, low-demand activities as the light fades.

Try instead: One familiar task at a time (towels, photo sorting), then shift into wash/comfort and dim/quiet phases.

7) “Caffeine doesn’t matter—it keeps them alert.”

Reality: Caffeine after noon often worsens late-day restlessness and disrupts sleep.

Try instead: Switch to caffeine-free tea or warm milk; use water with lemon for variety.

FAQ quick hits

- Q: What time does sundowning usually start?

A: Many caregivers see a rise in restlessness between 3 and 8 pm. Start your routine 90 minutes before the usual peak. - Q: Is melatonin helpful?

A: Sometimes, but results vary, and drug interactions exist. Ask the prescribing clinician; don’t start supplements on your own. - Q: Are mirrors and windows really a big deal?

A: Yes—reflections at dusk can look like strangers or doorways. Close curtains before dusk and cover problem mirrors. - Q: How do I handle repetitive questions?

A: Answer once with reassurance and add a visible note (whiteboard/sticky). Redirect to a simple, hands-on task. - Q: What’s one thing to do today that helps most?

A: Standardize the evening environment: lamps on, curtains closed, TV off/visuals calm, one task, then wash/comfort. Consistency beats intensity.